Honai (SVN) was a town made up mostly of Catholic refugees from the North and was known for having almost as many churches as houses. All seemed to be hastily slapped together in a jumble. The place had a desperate look and was always vulnerable to communist infiltration. No doubt among its few hundred anti-Communists there were many enemy agents.

One of the compounds in the Honai-section was the Ke Sat orphanage. Behind concertina wire gate and thick yellow walls several Vietnamese nuns cared for the lost children of the war--or tried to. One of the compounds in the Honai-section was the Ke Sat orphanage. Behind concertina wire gate and thick yellow walls several Vietnamese nuns cared for the lost children of the war--or tried to.

When assigned to the 3rd SPS, and on a second tour at Biên Hòa, I often visited the compound in off-duty hours with Med Cap teams and other Army and Air Force personnel able to get off base for civic-actions work, which helped break the monotony of on-base duty. Getting permission to go off base wasn't always easy, especially for those assigned to the 3rd SPS, as we were often on alert status, but a few did. Most CO's didn't figure an unsecured settlement of northern refugees was a great place for their troops to hang out in off-duty time. Nevertheless, in 1969, several NCO's, did manage to build a orphans' dormitory there.

The problem at Ke Sat, like other war orphanages, was there were more kids coming in than could properly be taken care of, even with the help of USAF and Army medical personnel visiting weekly. Mothers who were ARVN widows would occasionally leave their babies (often, of mixed Vietnamese with GI fathers) with the nuns. And through the gates of Ke Sat there was a brisk business in abandoned babies, many of them wounded, all sick. The nuns took them all and worked heroically to protect them, while they themselves lived in considerable danger, given their location.

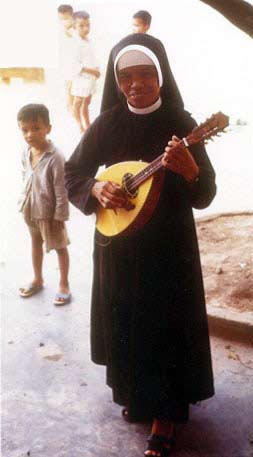

The sister who was my contact at the orphanage like to be called "Twiggy," (photo, left) a name some GI had given her a year earlier. After medicine and food for her children, the thing she wished most for was to be allowed to drive our jeep. She would hop in at a moment's notice, but we always managed to protect that bit of government property. The sister who was my contact at the orphanage like to be called "Twiggy," (photo, left) a name some GI had given her a year earlier. After medicine and food for her children, the thing she wished most for was to be allowed to drive our jeep. She would hop in at a moment's notice, but we always managed to protect that bit of government property.

Twiggy's grimmer duty was to take-in babies and save those she could--which weren't many. Priority went to the children who had survived infancy and might make it to adulthood. We'd look at those kids and wonder if they'd grow up to be war fodder as so many of their fathers had.

Twiggy took me into that stinking room, and watched for my reaction. Of course, she wanted Americans, those who might help, to see the suffering. There were about twenty babies lying on thin rags on the concrete floor, several in puddles of urine. Most of the babies had skin diseases as evidenced by white or red scabby patches. Their mucus-smeared faces were blank, eyes crusty with pus, and whimpering weakly. Americans who saw this kind of pathetic sight in Vietnam, could not have helped but contrast it with spotless maternity wards in hospitals back in "The World."

A couple of Vietnamese women were seeing to the needs of the babies, when possible, but the orphanage was filled with older children's conditions demanded care and attention. And most seemed to be suffering some combination of respiratory, skin, and eye diseases.

The next week when I visited Honai there were still ten of the babies in the nursery, with one or two crying more robustly. I had hoped they might survive, but realized it was chancy. Too many of the babies were too far gone when they had arrived, and a new crop of infants and babies lined up along one side of the room.

Without thinking, I asked Twiggy, "What happened to all the other babies from last week?" Though it must have seemed a stupid question to her, the nun reported patiently,

"Beau coup baby die."

The next few weeks were a High Threat of enemy action in the Biên Hòa area, and a lot of enemy movement was reported. The battle-hardened Đồng Nai Regiment of North Vietnam's Army was supposed to be gathering, and the Honai sector was strictly off-limits. The next few weeks were a High Threat of enemy action in the Biên Hòa area, and a lot of enemy movement was reported. The battle-hardened Đồng Nai Regiment of North Vietnam's Army was supposed to be gathering, and the Honai sector was strictly off-limits.

When we were able to return to the orphanage one Saturday morning, we were met at the gate by Sister Twiggy. She was smiling as usual through all the troubles. We delivered supplies, and told the sister yet again we couldn't let her drive the jeep. The USAF dentist with me began examining and treating the older children. As I walked through the compound, I neared the nursery and turned to look in, but Twiggy quickly blocked my way.

"You no look--no see," she warned, still smiling.

I had seen the orphanage over-crowed before and new the nuns were sensitive to room's appearance. "Many new kids this week?" I asked, as I stood near the doorway. The room was eerily quiet. Something was wrong. No crying or whimpering or anything.

She looked down and said in a low voice, "All baby die."

I have no idea if all the babies had died. It's hard to believe that twenty or thirty of them had all died in so short a time, but I knew that many had died, and more would die. And had seen the empty beds and cribs were children slept fitfully the day before. I knew that some of the kids would make it farther along the hard life that was a Vietnamese war orphan. And I knew that many would not. The Sisters' desperate need for help was all too real, and more than we could provide.

Decades later, it is the quiet room I hear in my dreams, and not the crying room of living children. |