Most Americans who weren't there know little of the civic action works thousands of soldiers, sailors, marines, and airmen volunteered for in Vietnam. In my own unit, the 3rd Security Police Squadron, Biên Hòa, 1969-1970, there were many who wanted to do civic action work off base but were unable to due to the frequent attacks and a CO who wanted the troops on full alert most of the time.

Nevertheless, several of our men managed to join others from Army and Air Force units in the Biên Hòa-Long Binh "rocket alley" area, helping the Vietnamese build schools, irrigation projects, and medical facilities in surrounding towns and villages. A project they were particularly proud of was the construction of a dormitory for the Ke Sat orphanage in the refugee town of Ho Nai north of the base.

The men in our unit also often served as guards on medical visits our doctors and nurses made to hamlets and villages. I'd like to say my own visit with a medical team to the leper colony we called Ben San was out of some kind of noble impulse to help on my part, but I'm afraid it was just a response to a wager MD Col. Martinez from our dispensary made with me. He bet me I wouldn't have the guts to go with him to deliver supplies to an isolated leper colony where we would mingle "up close and personal" with the lepers. Father Bissett's leper colony, was supplied by the Biên Hòa and Long Bihn medicos (I was station with 3rd SPS 69-70 and had a second tour as Chief of Admin there).

Ugly movie images of rotting sufferers (remember Ben Hur?) loomed in my dreams the night before we took off in a 101st Airborne Huey with supplies for the colony. That morning, as I sat on my flak jacket, I had less anxiety about taking ground fire than about being accidentally touched by one of those decaying lepers down there, an infecting touch that might condemn me to life in the colony. But I was determined to win the bet. And then there was my sheer, morbid curiosity.

The colony LZ was a small patch of red dirt cut out of the heavy surrounding forest. There, vulnerable (especially at night) to an enemy not known for his kindness to priests and nuns, Father Bisset and Vietnamese Sisters worked day in and day out to heal and protect those who were lucky enough to have "escaped" to the colony. The colony LZ was a small patch of red dirt cut out of the heavy surrounding forest. There, vulnerable (especially at night) to an enemy not known for his kindness to priests and nuns, Father Bisset and Vietnamese Sisters worked day in and day out to heal and protect those who were lucky enough to have "escaped" to the colony.

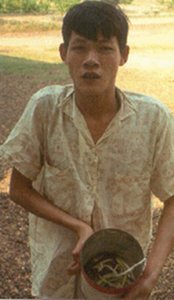

A surprisingly young-looking Father came forward with a welcoming bottle of wine, but around him skipped a skinny teenager with deformed limbs. When the boy offered me the Christmas "present" writhing furiously in a large bean can, Dr. Martinez grinned broadly. 'Well, you've got to take it to be polite." A surprisingly young-looking Father came forward with a welcoming bottle of wine, but around him skipped a skinny teenager with deformed limbs. When the boy offered me the Christmas "present" writhing furiously in a large bean can, Dr. Martinez grinned broadly. 'Well, you've got to take it to be polite."

I took the snake on its string leash, being careful not to touch the boy. The Father laughed. "It's not poisonous. Just carry it around for a while. We'll dispose of it later when the boy is gone. Although you may want to eat it. The boy is a very good snake hunter."

We proceeded with a tour of the colony, which I soon saw was an island of peace in the midst of conflict. No wonder Father Bisset had trouble keeping the place from being overrun even by healthy refugees trying to escape the war.

There were neat rows of huts for the families of the lepers, a dispensary, workshops and gardens. In one a woman with a sunken nose sifted colors into ceramic tile molds. In another a man with tools strapped the stubs of his hands worked as the colony tinsmith. Other workers made truck-tire sandals -- Hô Chi Minh sandals when the VC got hold of them.

More than once the VC had invaded this vulnerable colony, grabbing medical supplies and equipment. (Around this time at another leprosarium, Ban Mê Thuột East Air Field and Camp Coryell, they kidnapped nurses who were never heard from again.) I had seen many acts of courage by our men and women serving in Vietnam, but I had never seen any greater examples of courage than were presented by the doctor and sisters who served here "in harm's way" for so many years. Veterans everywhere know that if war often destroys our faith in the human spirit, the example of such individuals as these can also restore that faith.

In the dispensary we found an old man dying while a Sister tried to wave the persistent tropical flies away from his eyelids and lips. The Father told me Dr. Martinez had on an earlier trip agreed to be the old man's "godfather" and that he believed the patient held off death until he could once again see his benefactor. He and the American doctor talked quietly for several minutes. Before we left that day, the old man died.

It didn't take long before my fear of the lepers began to fade. The children at times seemed like kids everywhere. For many the disease was well under control thanks to sulfa drugs and other treatments.

Those in the more advanced stages, some of whom had been cut off from treatment by regional battles, seemed to have less hopeful prospects. As we lifted off, the children gathered to sing a Christmas carol to us. Their voices were ragged, not beautiful. Although there was a hint of hope there, there was also one of desperation.

I have to admit that when we got back to base, I felt compelled to wash up thoroughly - several times.

If my own motives for going were questionable at best, the experience had served to remind me that there will always be those like that chopper pilot, like Dr. Martinez, like the father and sisters of the colony, who will take great risks to serve others.

America and the rest of the world needs to hear their stories as well as the stories of thousands of others who served, when they could, with great decency and caring through the many civic actions programs during this nation's longest war.

Paul Kase |