Đà Nàng

Air Base - 1969

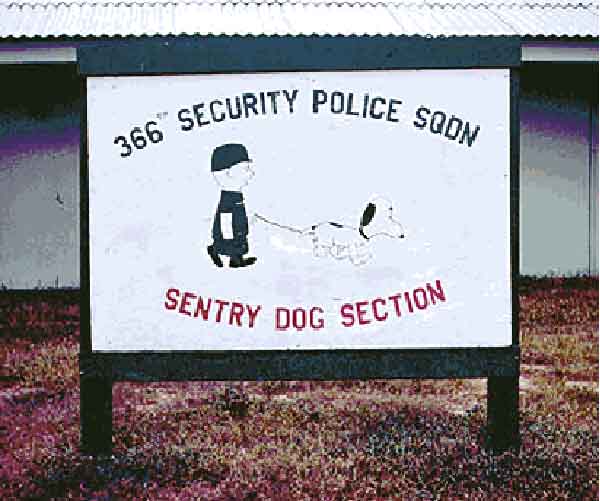

In early

1969, the Air Force Sentry Dog Section at Đà Nàng Air Base

consisted

of approximately 45  sentry

dog teams, one kennel attendant, and the kennel master. The kennel

master, SSgt Carl Wolfe, whom later taught at the Dog School

at Lackland AFB, Texas in the mid-70's. The dog teams worked on

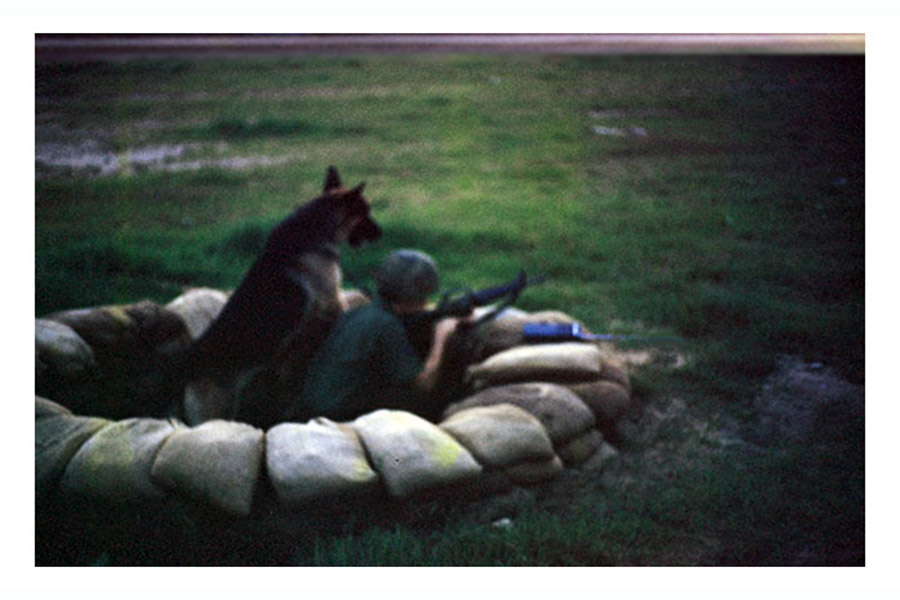

the base perimeter between defensive M60 machine gun positions

and the actual perimeter fence.

sentry

dog teams, one kennel attendant, and the kennel master. The kennel

master, SSgt Carl Wolfe, whom later taught at the Dog School

at Lackland AFB, Texas in the mid-70's. The dog teams worked on

the base perimeter between defensive M60 machine gun positions

and the actual perimeter fence.

The machine gun bunkers were at the

rear corners of our posts. We only had one post located on the Air

Force side of the base and 37 posts alongside three Marine companies

from the 3rd MP Battalion.

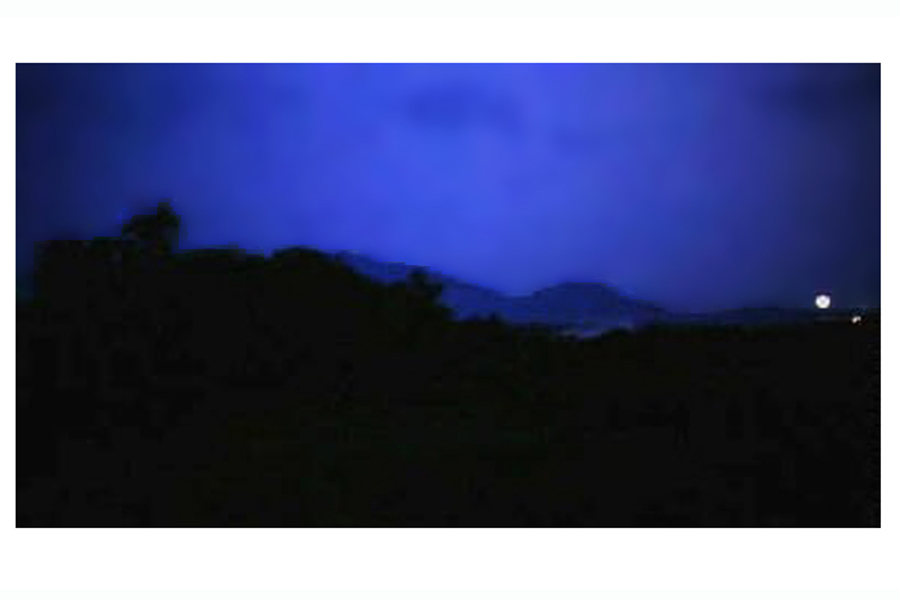

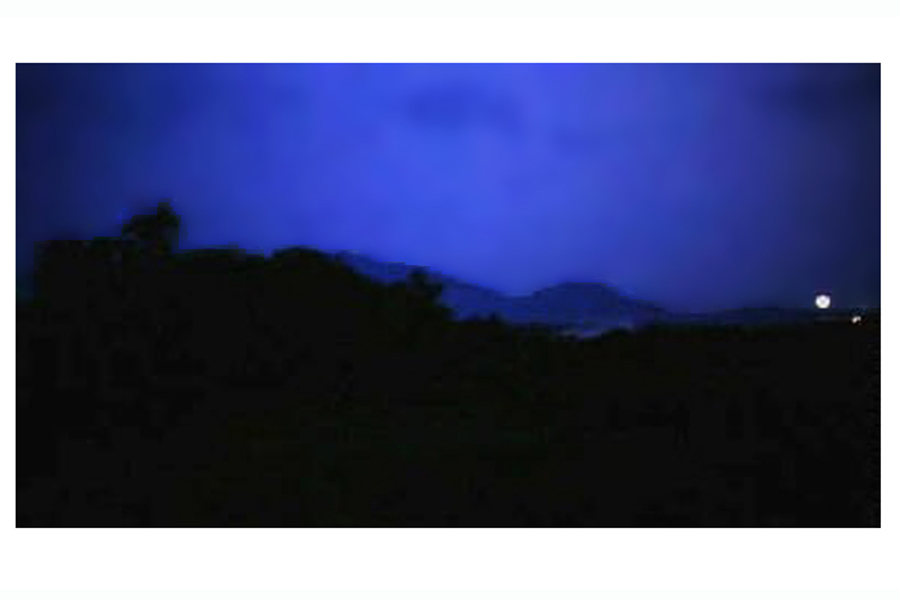

We also had

two posts located in the base Bomb Dump (photo below), located near

an ARVN camp and the Marine ammo dump. One thing's for certain;

it got very dark there! From time to time, special posts were developed

as needed, such as the temporary post located in the interior of

the Napalm dump. This was not a popular place to be during a rocket

attack.

The dogs were the seasoned veterans and deserved all of the credit.

Handlers came, spent a year and rotated home. Most of the dogs however

stayed forever. Only a few were allowed to rotate to other bases

outside of Vietnam. But while they were alive, they received better

care than most GIs. Unfortunately, they were put to sleep when they

were unable to work anymore.

Most dogs were males. But every kennel usually had a least one female

dog. We had one named Cinder. Cinder was the most lovable

dog in the section, not a mean or aggressive bone in her body. Jerry

Cox, who rotated to Đà Nàng after a tour at Kadena Air Base,

Okinawa, handled Cinder. Cinder did not bite very well but could

she alert! As Jerry often said, if someone farted on the perimeter

he knew it.

Most dogs were males. But every kennel usually had a least one female

dog. We had one named Cinder. Cinder was the most lovable

dog in the section, not a mean or aggressive bone in her body. Jerry

Cox, who rotated to Đà Nàng after a tour at Kadena Air Base,

Okinawa, handled Cinder. Cinder did not bite very well but could

she alert! As Jerry often said, if someone farted on the perimeter

he knew it.

The biggest dog was Lance,

always weighing over 100 pounds. Any dog that weighed over 100 lbs.

in Southeast Asia, was the size of a small horse. Everything about

Lance was big, including feet, head, body, and especially teeth.

Lance's neck was so big that a regular choke chain wouldn't fit

over his head. His choke chain was improvised from the "old" kennel

chains that had a choke chain in one end. Lance was prone to turn

on his handler, but he would let anyone take him out of the kennels,

because he loved to play catch. You just didn't give him any commands.

Lance and his handler had been in the one of the bomb dumps when

it had been blown up. They crawled out using the ditches.

The most mean spirited dog in the

section had to be Blackie. Blackie  was big, not huge like Lance, but tall and lanky. I handled Blackie,

briefly, but as I only outweighed him by about 30 pounds, it didn't

work out. I weighed 120 pounds and was nicknamed "Twig" by the handlers

(no, they didn't kick sand in my face!). Five VSPA members handled

Blackie from 1965 to 1970! Blackie would take his chow pan to the

back of his kennels and dare you to come in and get it. The number

of chow pans, stored in Blackie's kennel, reflected the number of

days that his handler had been gone. Blackie had been taught to

carry a helmet in his mouth for his handler. His neck muscles had

developed to where he could pick up a full water bucket and sling

it across his kennel. The bucket had to be clipped to a fence. He

would "empty" his bucket, and then try to bite you for turning

it over and refilling it. Blackie did bite at least one of his own

handlers.

was big, not huge like Lance, but tall and lanky. I handled Blackie,

briefly, but as I only outweighed him by about 30 pounds, it didn't

work out. I weighed 120 pounds and was nicknamed "Twig" by the handlers

(no, they didn't kick sand in my face!). Five VSPA members handled

Blackie from 1965 to 1970! Blackie would take his chow pan to the

back of his kennels and dare you to come in and get it. The number

of chow pans, stored in Blackie's kennel, reflected the number of

days that his handler had been gone. Blackie had been taught to

carry a helmet in his mouth for his handler. His neck muscles had

developed to where he could pick up a full water bucket and sling

it across his kennel. The bucket had to be clipped to a fence. He

would "empty" his bucket, and then try to bite you for turning

it over and refilling it. Blackie did bite at least one of his own

handlers.

In 1969, Blackie was handled by Clarence

Dedecker III. Dedecker had the right size and disposition for

Blackie and solved a problem we had been having with our vet. The

veterinarian was prone to "antagonize" any dog brought in for exams.

The handlers had discussed the issue, but were undecided as to what

action to take. Dedecker solved the problem for during one of Blackie's

vet appointments. Dedecker put a muzzle on Blackie and entered the

clinic. The vet teased the dog; Dedecker dropped the leash and off

went Blackie. He chased the vet around the table and pinned him

in the corner. Blackie was trying to rub his muzzle off on the vet's

chest, so he could return the "teasing". Dedecker was just a little

slow in recovering Blackie, and apologized for the leash "slipping".

No damage occurred, but the vet never teased another dog.

The most aggressive dog on post was Baron. He was just average sized dog. But his goal in life

was to bite anyone within 10 miles of his handler. Baron would even

try to nail another handler for talking to his handler on post.

He would be quiet, then without any warning hit the end of his leash

like a rocket. His handler could never relax and talk with anyone.

I don't remember his name; never BS'd with him on post. He would

even ignore Cinder, just give Jerry Cox the evil eye, until he thought

he could sneak in a quick bite.

We had some character dogs

also. One dog named Shep (referred to as Crazy Shep)

actually enjoyed puncturing jeep tires with his teeth. Another dog

named Sugar started the anti-smoking trend decades before

it became popular. If you blew smoke into the air, Sugar would jump

into the air and snap at it. The dog least likely to be mistaken

for a German Shepherd was a big hound dog named Marblehead.

He looked and sounded like a Blue Tick hound, but he had a hell

of a nose and was fairly aggressive. If Cinder could hear a fart

anywhere on the perimeter, Marblehead could smell one anywhere in

Vietnam.

Newcomers to the three Marine companies,

Alpha, Bravo and Charlie, were always surprised to find Air  Force

dog teams patrolling with them at night on the perimeter. All of

the handlers preferred to work the Marine perimeter rather than

Air Force posts. Alpha CO lines ran from the main Air Force

cantonment area to a gate located on the south side of the base.

The road out of this gate ran past a silk factory, leading to one

of the bridges over the river. I think the road ran in the direction

of Happy Valley (A popular launching point for VC rockets).

Alpha CO's CO was a Captain Swartz. He checked posts

almost every night, and usually stopped to talk to each handler.

We regarded him as having brass ones because of the way he ignored

dogs agitating on him. He would walk up so close that it took a

determined effort to prevent a dog from biting him.

Force

dog teams patrolling with them at night on the perimeter. All of

the handlers preferred to work the Marine perimeter rather than

Air Force posts. Alpha CO lines ran from the main Air Force

cantonment area to a gate located on the south side of the base.

The road out of this gate ran past a silk factory, leading to one

of the bridges over the river. I think the road ran in the direction

of Happy Valley (A popular launching point for VC rockets).

Alpha CO's CO was a Captain Swartz. He checked posts

almost every night, and usually stopped to talk to each handler.

We regarded him as having brass ones because of the way he ignored

dogs agitating on him. He would walk up so close that it took a

determined effort to prevent a dog from biting him.

I believe that Bravo CO had

two platoons, one on each side of the bridge over the river. One

of platoons was overrun and had to withdraw back across the river.

They retook the bridge but suffered casualties. On Đà Nàng, Bravo

CO lines were short with only two platoons on the perimeter.

The aforementioned silk factory was located at the gate, off base

next to the perimeter fence. Past the gate, Bravo CO lines

were on the perimeter fence with the on base bomb dump behind them.

We only had a few posts there. They were between the perimeter fence

and an inner chain link fence, with a road used only in the daytime

and a high dirt revetment separating the perimeter from the bomb

dump. The on base bomb dumps were as far away from the flight line

and cantonment areas as possible, yet still within the base perimeter.

Charlie CO lines were the longest. They stretched from the

POL tank  farm on the northwest Marine side of the base, around a large swamp

that was north of the ends of the two parallel runways, to the POL

tank farm located on the northeast Air Force side. In the area where

the swamp ran off base, the fence consisted of some concertina and

a few strands of barbed wire. Charlie CO controlled two vehicle

gates to the base.

farm on the northwest Marine side of the base, around a large swamp

that was north of the ends of the two parallel runways, to the POL

tank farm located on the northeast Air Force side. In the area where

the swamp ran off base, the fence consisted of some concertina and

a few strands of barbed wire. Charlie CO controlled two vehicle

gates to the base.

Our posts, beginning with Kilo-1,

were between bunkers manned by 1st Platoon, Charlie CO, with

the last post on Charlie CO lines being Kilo-14. Kilo-15 was

on the Air Force side. Kilo-16 started the Alpha CO lines.

The area of the silk factory was

the scene of sapper and sniper activity in the Tet of 1968 and 1969.

Some of us had to low crawl from our posts during those attacks.

In the Feb 23, 1969's attack, VC moved into the silk factory, located

near the base perimeter. Alpha CO attempted to take the factory,

but met with heavy resistance, with one Marine killed. The VC were

hiding in large drainage pipes under the floor. The Marines contacted

the 366th SPS and asked for dog teams

to go into the drains. By this time most of us were in the rack

attempting to sleep despite the noise, small arms fire, F-4's taking

off and explosions. The first two handlers found in the hut area

agreed to go. When the dog teams entered the drainage pipes, the

VC immediately fled into the factory. Alpha CO then took the

factory with no more friendly causalities. I think that one of the

handlers was Gary Beck, handling Sparky. Gary and

I shared a cube together in the party hut. Before he rotated

he had to take Sparky to Long Bien to be put to sleep. In

those days, handlers had to take their own dog's to all vet appointments,

no excuses. I was glad that none of my dogs I had handled was put

sleep while I was there.

The Freedom Bird due to land that

morning, circled the Air Base for several hours before landing.

When it finally did land, fires were still burning from the attack.

That flight also brought in about seven new handlers from a pipeline

USAF sentry dog class. Three of those handlers were Bill Grife,

Gill Perry and Pete Koenig. They later described how

it felt circling the base, looking down at the smoky fires. Talk

about a welcome wagon!

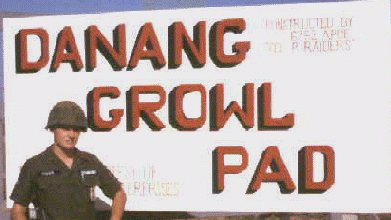

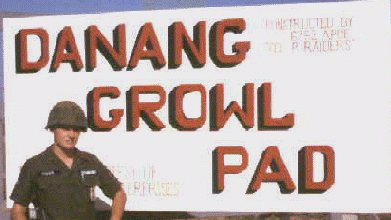

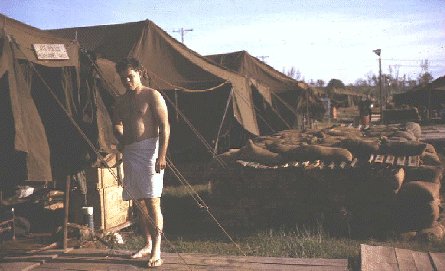

The Air Force Đà Nàng kennels, known

earlier as the Growl Pad, had been located near the Air Force

area on base, then known as Tent City. USAF military police were

then called "Air Police Squadrons", but were later redesignated

as "Security Police Squadrons."

In the below photo, a large blue

water tank can be seen atop the K-9 Admin. office of 1966. The tree

line was bulldozed back 500 yards for a clear fire zone.

By my late 1968 arrival in country, the kennels had been moved to

the side of the base near the terminal and the main compound housing

base headquarters. The old kennels was located just off of the main

perimeter road that circled the base, behind a SAC detachment and

had a POL tank farm located on the north side. Charlie CO's

last bunker was near the rear of the kennels. The kennel was located

behind a SAC detachment.

The new kennels had a steel roof

over the cinder block and chain link dog kennels. An air-conditioned

kennel support building housed the office, supply room, kitchen,

and the veterinarian's office.

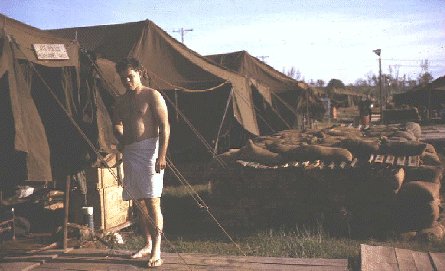

Security Police lived in a compound

between the base headquarters compound and the main AF compound.

Originally, the Squadron lived in tents, but we lived in old barracks

that had been built by the French. We went out on patrol at night

and worked along side Marines, but came back in the morning to the

infamous luxuries of the Air Force side of the base.

Handlers lived in one of two huts.

One hut was for the party crowd, the other for the more sedate handlers.

The party-hut had a "get together" every morning. A few drinks (the

definition of a few drinks varied for some of the guys!) and we

would hit the rack and attempt to sleep until the heat of the day

and aircraft noise woke us up. We would go have our evening meal

in the chow hall, then started getting ready for posting.

Our weapons were kept in our wall

lockers, at least until a SP shot up the NCO hut. The gunplay took

place in the hut, next door to the K-9 partying hut. An armory was

quickly (late 1969) built thereafter, and we had to turn in all our

weapons and check them in and out.

By late 1969, most airmen lived in

open bay barracks. Most barracks were divided up into cubes consisting

of a pair of bunk beds facing two metal wall lockers. Industrious

individuals attempted to scrounge or make furniture to fit into

the space between the lockers. Plywood, impossible to find and seldom

seen in the barracks, was the exception, of course, in the K-9 barracks.

One of our dog posts was between the perimeter fence and a supply

yard that contained lumber. So needless to say, our huts were finished

a little nicer in our quarters from recovered stuff dropped by those thieving Viet Cong. We had walls between cubes and wood flooring

over the concrete slab. The floors raised us above the "high tide"

caused by monsoon flooding.

A new base commander decided that

all the barracks should revert back to the open bay type and ordered

the "cubes" removed. Of course, the Security Police Squadron Commander

was the first to jump on it. All the other units dragged their feet.

Our Commander directed all cubes removed within a week! Every hut

started tearing down the cubes a little bit every day. Except the

K-9 Party Hut... we had a few drinks every morning and watched

everyone else tear down their cubes. Everyone had worked so hard

to have a little piece of the world in the form of a cube. When

the last morning arrived, we held probably the most destructive

K-9 party ever. Well, they did order us to tear down the cubes.

You know what happens when you tell

a dog handler to destroy something. Non-dog handlers walking past

the doors paused to watch the festivities. Soon lumber, beer cans,

and liquor bottles were being ejected out the door in a contest.

Our version of "mine is bigger" was changed to "I can throw my cube

farther than you can throw yours." Complaints were made to the proper

authorities, in reference to irreverent comments and actions being

observed. Law Enforcement (Security Police) responded but only peeked

in through the open doors.

One handler (unnamed to protect the

guilty) sang loudly as he sat atop the revetment surrounding the

hut. He taunted non-canine-types by betting them $20 they couldn't

make it unscathed through the hut and out the other end! No one

took him up on the bet. The irreverent crooner was also the obvious

source of rude comments to officers passing near his revetment post.

The First Sergeant, who happened to have bright red hair and no

sense of humor, responded to restore order. This handler sang him

a little ditty at maximum volume in a slurred voice that was not

well received by the First Sergeant. It's more polite lyrics (this

is a family page) consisted of, "I'd rather be dead... than

red in the head... like the dick on a dog... woof, woof."

I was told the performance was rather well received by everyone

else. However, the First Sergeant's new goal in life became fetching

this handler from his perch and making his life permanently miserable--everyone

else's noise complaints were totally forgotten! I don't remember

too much of what occurred at the end of the party (don't read too

much into that), except the song became a new standard (at least

out of the First Sergeant's hearing).

When the hung over dog handlers started

waking up in the late afternoon, the kennel master, SSgt Frederick

Doctor, met us. He was moving into the hut as ordered by a certain

individual whose hair matched his anger at the rude and disrespectful

dog handlers, who were in need of close supervision.

The kennel master was not pleased

to leave the comforts of the NCO hut and being forced to live with

us. We were severely chastised for his embarrassment caused by our

actions. Our response was to have a welcome party the next morning

for him when we returned from post. Alcoholic beverages were not

banned from the barracks area. I guess that the powers-to-be preferred

our parties held in the compound instead of the Airmen's Club. Oh,

by the way, the Base Commander canceled his order to tear down the

cubes.

Life continued, and K-9 teams going on post were dropped off alongside

the main road and they walked to the perimeter. We then walked parallel

to the perimeter until reaching our assigned posts. Đà Nàng originally

had only one runway in 1965-1966, the second parallel strip was built

in 67-68.

As we walked past bunkers manned by Marines, we were always asked

if our dog knew any tricks. Handlers quickly learned that showing

off a few dog tricks would guarantee cordial relations (coffee)

with the Marines manning the bunkers. They would give up a sandwich

or two from the "midnight rations" delivered to the Marines on the

perimeter. The sandwich was a welcome break from the C-Rations that

we were given. The sandwich was always split with the most important

member of the sentry dog team, the dog, which always pleased the

marines.

Đà Nàng was nicknamed "Rocket City"

(to see why, check out Rocket City images and info on Đà Nàng AB) due to the large number

of attacks by 122mm and  140mm rockets. Most of the sentry dogs displayed a specific behavior

pattern or alert whenever there were incoming rockets or mortars.

These few seconds warning was greatly appreciated! We realized the

dog's superior senses were picking up on something, but there was

still an aura of mystique about this. I now realize that it was

just a case of pure Pavlov conditioning. The dog would hear a rocket

either going overhead or on a side of our location, and anticipate

the excitement (handlers become a little hyper when rockets are

exploding about) that always accompanied rockets. One dog Sugar,

would jump up and snap at the air! My dog, Kobuc, would start pulling

to the closest K-9 Fighting Bunker (always knew he was the smartest

dog around!). I only had to crawl; he would navigate.

140mm rockets. Most of the sentry dogs displayed a specific behavior

pattern or alert whenever there were incoming rockets or mortars.

These few seconds warning was greatly appreciated! We realized the

dog's superior senses were picking up on something, but there was

still an aura of mystique about this. I now realize that it was

just a case of pure Pavlov conditioning. The dog would hear a rocket

either going overhead or on a side of our location, and anticipate

the excitement (handlers become a little hyper when rockets are

exploding about) that always accompanied rockets. One dog Sugar,

would jump up and snap at the air! My dog, Kobuc, would start pulling

to the closest K-9 Fighting Bunker (always knew he was the smartest

dog around!). I only had to crawl; he would navigate.

In mid-1969, the off base munitions

dumps exploded and burned for hours early one morning after we had

just come in from post. The Marine kennels, located near the munitions

dumps, had to be evacuated. Their dogs were brought to our kennels,

staked out to the fence, with shipping crates used as doghouses.

I remember that one of the Marine handlers had his leg in a full

cast. After a few days, they were moved to the Navy sentry dog kennels

at China Beach.

A short time later a Marine K-9 party

was held at the Navy kennels for all of the Air Force Đà Nàng handlers.

I don't remember too much about the party (don't read too much into

that, either!); however, I do recall seeing the beach from the kennels.

I caught the K-9 posting truck in to the Air Base, but several AF

handlers stayed and joined a party of Marine and Navy handlers at

a nearby Army Club. Some soldiers decided to pick on the few Marines.

They soon found out that all the dog handlers were more than willing

to back each other.

A few of the lucky handlers were

off that night. Tom Suddeth woke up the next morning and

found himself at a Marine site. The only problem was that it was

at Marble Mountain. He made it back to the base in time for

Guardmount and work that night, thanks to friendly Marines.

By late 1969, the section had developed

into a very exclusive, tight group. Handlers were expected to stand

together on anything against anyone. It was very much a case of

us against everyone else. The only exception was the Marines. They

treated us better on post than our fellow Air Force Security Police

did, and we responded accordingly.

No one liked to work the only post

on the Air Force perimeter side of the base (Kilo15). We went through

a gate located near a machine gun tower. The SP at the tower would

then padlock the gate behind us. The post was between an inner chain

link fence and a triple row of concertina. Behind the concertina

was a row of Claymore mines, controlled by the machine gun tower.

A sandbag was located behind each mine to reduce the back blast.

The only other feature on the post was a K-9 bunker. We had been

told that if all the Claymores were fired, the only chance we had

to survive was to be in our little K-9 bunker. If you wanted to

sit down and enjoy your C-Rations, you could either sit atop the

bunker or sit on a sandbag and have a close up look at its companion

Claymore.

It was rumored that after one rocket

attack, the firing panel for the Claymores was found unlocked. The

handlers were not at all pleased with that. As I said earlier, the

new Marines were always surprised to find AF Dog Handlers in front

of their bunkers at night. Charlie CO had more of the Marine

perimeter (distance) than Alpha or Bravo Companies; thus, we had

plenty of friends with Charlie CO. The Marines had ambush teams

off base every night.

Our days off rotated by the number

of posts and the number of handlers.  There were 38 normal posts and 40 dog teams available, so two handlers

were off every night. When we were off, we made a night of the movie

theater and club, but we would usually end up at the kennel with

our dogs. Or, we would go out with the Marine squad to an ambush

site. This was always done without the knowledge or approval of

the squadron. We would either catch a ride with the posting truck

or the Marines would send the CO jeep to the kennels to pick

us up. When the squad returned to base the next morning, we would

catch the K-9 relief truck.

There were 38 normal posts and 40 dog teams available, so two handlers

were off every night. When we were off, we made a night of the movie

theater and club, but we would usually end up at the kennel with

our dogs. Or, we would go out with the Marine squad to an ambush

site. This was always done without the knowledge or approval of

the squadron. We would either catch a ride with the posting truck

or the Marines would send the CO jeep to the kennels to pick

us up. When the squad returned to base the next morning, we would

catch the K-9 relief truck.

We were the only Air Force personnel,

who drove out Charlie CO Gates without being questioned, if

the right Marines were on duty. On more than one occasion, the kennel's

deuce and a half (2 1/2 ton truck) made runs to certain establishments

located off base. During one of the runs, an argument ensued over prices and services to be rendered. The handlers involved

solved the argument by driving the truck through the vacated hut

in protest. The hut was constructed of bamboo with a thatched roof.

There was damage to the truck from an unforeseen encounter with

the electric pole located behind the hut. The front bumper and the

left fender had to be replaced. But no fear; for a few cases of

beer the Marine motor pool repaired the damage and no one was the

wiser. Of course the paint didn't match, but who cared. The handlers

involved will remain anonymous.

We sometimes would have to man special

posts when the squadron wanted to provide extra detection capability.

All of the handlers disliked one special post in particular. It

was a swamp, located between the Army Mortuary and Charlie CO

Lines. SP machine gun towers equipped with starlight scopes would

sometime spot movement in the swamp. Thus, it would usually result

in a dog handler being posted there for a few nights. The dog team

would be dropped off at the mortuary. You had to walk past the double

screen doors at the end to get to the post. You would say to yourself,

"I will not look in, I will not look in;" but it was as though someone

reached down, grabbed your head, twisting it to force you to look

at the body bags containing all those KIAs. Then, you walked past

the pallets of caskets and drums of embalming fluids. When a flare

was up, you could read the label painted on the drums. After that

you were in a great frame of mind, for the remainder of the night.

The post even had a small Buddhist temple located within its boundaries.

We would refer to this post as hunting for the "Phantom."

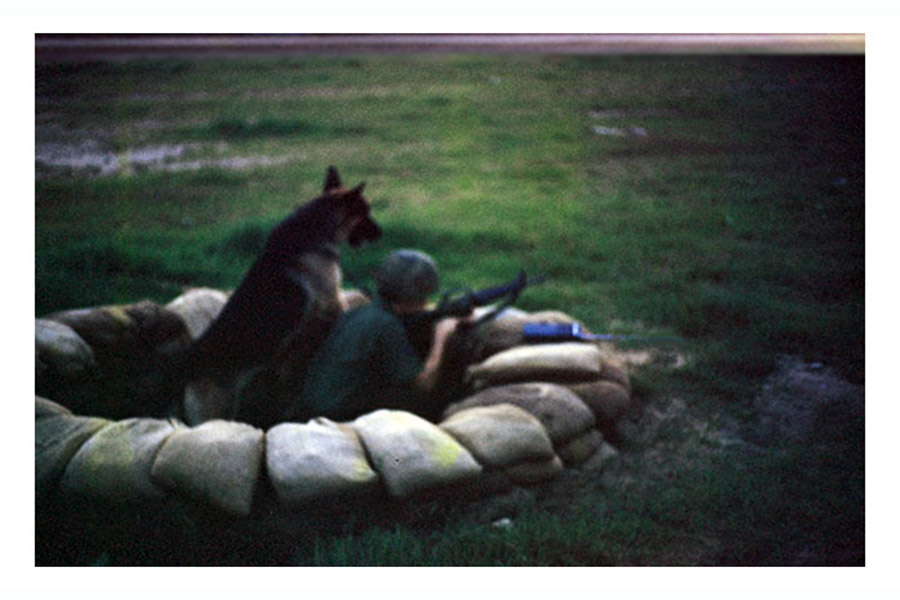

Our little K-9 bunkers were located

between the bunkers that formed the rear corners of this post. These

were built of a layer of sandbags, stacked outside small barrels

filled with sand. The bunkers had a roof made of two sheets of plywood.

This 8'x 8' roof hung over the bunker and made a welcomed haven

against monsoon rains. The bunkers were low enough so that you and

your dog could look over the top. This forced you to crawl on your

hands and knees into the bunker. When preparing to enter the bunker

the dog would normally enter first. You would almost have to get

on your hands and knees to crawl in. You and dog could sit there,

on your comfortable sandbag seat, and both of you could look over

the top of the wall.

One night my dog didn't want to go

into the bunker. I always dropped off a field pack that contained

extra ammo, C-Rations and 2 water canteens. I would return to the

bunker throughout the night. I had placed the pack on the wall next

to the entrance. But Kobuc didn't run in like he normally did. As

a matter of fact, he locked up all four paws! An experienced handler

always stayed behind the smarter member of the team. The golden

rule for a handler is: "If dog doesn't want to go there---you

don't want to go there." Hence, I did the prudent thing; I dropped

off my stuff elsewhere.

The next morning the kennel attendant

made his usual once a week rounds to  pick up equipment left on post. He started into the bunker and found

a large Krait snake coiled up, and very unhappy at being

disturbed. Like the Cobra's venom, the Krait's venom is neurotoxic

and signs of paralysis may appear within minutes or be delayed for

hours. That afternoon, I was told about the snake and asked if I

had entered the bunker the night before. I made immediate plans

to treat the smarter member of the team to a steak dinner from the

NCO Club. Kobuc really enjoyed the rare steak I bought him!

pick up equipment left on post. He started into the bunker and found

a large Krait snake coiled up, and very unhappy at being

disturbed. Like the Cobra's venom, the Krait's venom is neurotoxic

and signs of paralysis may appear within minutes or be delayed for

hours. That afternoon, I was told about the snake and asked if I

had entered the bunker the night before. I made immediate plans

to treat the smarter member of the team to a steak dinner from the

NCO Club. Kobuc really enjoyed the rare steak I bought him!

The bunkers provided a nice sitting

area if you wanted to hop up on the roofs, which were maybe 3-4

feet off the ground. We had received heavier than normal rainfall

and the low lying areas on base had flooded. The Vet decided that

his dogs were not going to be on flooded posts. So, the dogs stayed

in the nice dry kennels and we went out on post without them. I

was on Charlie CO lines. The swamp behind the bunker line had

turned into Lake Đà Nàng. It was not hard to imagine the snakes

swimming around hunting for a dry place. And there you were sitting

on top of a prominent island. Without the more intelligent team

member to talk to it was a long, lonely night on post. It was miracle

we found our way to the relief trucks in the morning. The next night

the water level had dropped, so we were okay. Oh, yes, the snake-infested

bunker had been on Charlie CO lines also.

[Photo, Krait Snake: This black and white banded snake is nocturnal

and one of the most dangerous snakes in Asia, and bite readily at

times and without hissing. In addition to this, the bite is virtually

painless, and victims may neglect to seek proper treatment. Deaths

from this snake are probably under reported, since most occur at

night and unattended.]

In mid to late

1969, we had two other Kennel Masters, each for a short duration.

One was SSgt Doctor; the other was TSgt Faust, who

wasn't a dog handler. Both went home for emergency reasons. By 1969,

many Air Force K-9 handlers were on their second 'Nam tour. The

Air Force had more dogs in Vietnam than elsewhere, so it was a

revolving assignment for handlers with a four-year enlistment. Handlers

would pull a 'Nam tour, go back to the world, and several months

later have orders for 'Nam again. Sydney Hillard, Comer,

and several others had been in 'Nam at other bases. Many handlers

came to 'Nam from other overseas bases. Cox PCS'd from Okinawa,

and Bill Humpla from the Philippines.

The size of the Sentry Dog Section

at Đà Nàng Air Base varied depending on the number of posts manned.

In January 1970, the section was reduced while I was on my 30-day

"free" leave for extending. Upon my return, I discovered that nine

other handlers and I were transferred to Phu Cat Air Base.

All excess dogs were shipped to other units. Blackie went

to Tan Son Nhut Air Base. My dog Kobuc was shipped

to Phu Cat Air Base.

It is my understanding that the Đà Nàng K-9 section was increased in size again sometime in 1970. Thanks

to the Vietnam Dog Handler Association,

I have been able to contact another handler who worked Kobuc after

I did: Steve Jannick. Steve and I have shared pictures and

fond memories of "our dog Kobuc," whom we both loved. Kobuc in turn

had given each of us his love, too.

There aren't

anymore Vietnam dog handlers on active duty. I wish that other

handlers would combine their personal experiences in their sections

or units so that a history of the military dog program could be

recorded or perhaps compiled. War Dogs should be remembered for

the unselfish sacrifices they made and the lives they saved.

I didn't arrive in Vietnam as a

dog handler. Two months into my tour, I answered a call for volunteers

for the dog section. Tom Suddeth, Bob Laruritsen, Dennis Alexander

and I were trained OJT by the Kennel master, SSgt Carl Wolfe.

We learned that the squadron wanted all dogs on post in time for

the 1969 Tet. We had one week of training with one scouting problem

before we went on post. We were the rookies and the seasoned dogs

were the pros. My first night on post, handlers from both sides

came down to check on me and give advice. The first and last thing

I was told, "Trust your Dog!" The handlers had welcomed us into

the brotherhood.

I made the military a career and

retired in 1987. I had a tour of duty at two of the three Air Force

Dog Schools that were in existence. I have handled and/or taught

Sentry, Patrol, Drug Detector, and Explosive Detector Dogs. I always

considered myself a dog handler first and last. When I go to sleep

at night, I still sometimes dream of a beautiful silver-black Shepherd

and of posts in a far away land.

sentry

dog teams, one kennel attendant, and the kennel master. The kennel

master, SSgt Carl Wolfe, whom later taught at the Dog School

at Lackland AFB, Texas in the mid-70's. The dog teams worked on

the base perimeter between defensive M60 machine gun positions

and the actual perimeter fence.

sentry

dog teams, one kennel attendant, and the kennel master. The kennel

master, SSgt Carl Wolfe, whom later taught at the Dog School

at Lackland AFB, Texas in the mid-70's. The dog teams worked on

the base perimeter between defensive M60 machine gun positions

and the actual perimeter fence.

Most dogs were males. But every kennel usually had a least one female

dog. We had one named Cinder. Cinder was the most lovable

dog in the section, not a mean or aggressive bone in her body. Jerry

Cox, who rotated to Đà Nàng after a tour at Kadena Air Base,

Okinawa, handled Cinder. Cinder did not bite very well but could

she alert! As Jerry often said, if someone farted on the perimeter

he knew it.

Most dogs were males. But every kennel usually had a least one female

dog. We had one named Cinder. Cinder was the most lovable

dog in the section, not a mean or aggressive bone in her body. Jerry

Cox, who rotated to Đà Nàng after a tour at Kadena Air Base,

Okinawa, handled Cinder. Cinder did not bite very well but could

she alert! As Jerry often said, if someone farted on the perimeter

he knew it. was big, not huge like Lance, but tall and lanky. I handled Blackie,

briefly, but as I only outweighed him by about 30 pounds, it didn't

work out. I weighed 120 pounds and was nicknamed "Twig" by the handlers

(no, they didn't kick sand in my face!). Five VSPA members handled

Blackie from 1965 to 1970! Blackie would take his chow pan to the

back of his kennels and dare you to come in and get it. The number

of chow pans, stored in Blackie's kennel, reflected the number of

days that his handler had been gone. Blackie had been taught to

carry a helmet in his mouth for his handler. His neck muscles had

developed to where he could pick up a full water bucket and sling

it across his kennel. The bucket had to be clipped to a fence. He

would "empty" his bucket, and then try to bite you for turning

it over and refilling it. Blackie did bite at least one of his own

handlers.

was big, not huge like Lance, but tall and lanky. I handled Blackie,

briefly, but as I only outweighed him by about 30 pounds, it didn't

work out. I weighed 120 pounds and was nicknamed "Twig" by the handlers

(no, they didn't kick sand in my face!). Five VSPA members handled

Blackie from 1965 to 1970! Blackie would take his chow pan to the

back of his kennels and dare you to come in and get it. The number

of chow pans, stored in Blackie's kennel, reflected the number of

days that his handler had been gone. Blackie had been taught to

carry a helmet in his mouth for his handler. His neck muscles had

developed to where he could pick up a full water bucket and sling

it across his kennel. The bucket had to be clipped to a fence. He

would "empty" his bucket, and then try to bite you for turning

it over and refilling it. Blackie did bite at least one of his own

handlers.  Force

dog teams patrolling with them at night on the perimeter. All of

the handlers preferred to work the Marine perimeter rather than

Air Force posts. Alpha CO lines ran from the main Air Force

cantonment area to a gate located on the south side of the base.

The road out of this gate ran past a silk factory, leading to one

of the bridges over the river. I think the road ran in the direction

of Happy Valley (A popular launching point for VC rockets).

Alpha CO's CO was a Captain Swartz. He checked posts

almost every night, and usually stopped to talk to each handler.

We regarded him as having brass ones because of the way he ignored

dogs agitating on him. He would walk up so close that it took a

determined effort to prevent a dog from biting him.

Force

dog teams patrolling with them at night on the perimeter. All of

the handlers preferred to work the Marine perimeter rather than

Air Force posts. Alpha CO lines ran from the main Air Force

cantonment area to a gate located on the south side of the base.

The road out of this gate ran past a silk factory, leading to one

of the bridges over the river. I think the road ran in the direction

of Happy Valley (A popular launching point for VC rockets).

Alpha CO's CO was a Captain Swartz. He checked posts

almost every night, and usually stopped to talk to each handler.

We regarded him as having brass ones because of the way he ignored

dogs agitating on him. He would walk up so close that it took a

determined effort to prevent a dog from biting him.  farm on the northwest Marine side of the base, around a large swamp

that was north of the ends of the two parallel runways, to the POL

tank farm located on the northeast Air Force side. In the area where

the swamp ran off base, the fence consisted of some concertina and

a few strands of barbed wire. Charlie CO controlled two vehicle

gates to the base.

farm on the northwest Marine side of the base, around a large swamp

that was north of the ends of the two parallel runways, to the POL

tank farm located on the northeast Air Force side. In the area where

the swamp ran off base, the fence consisted of some concertina and

a few strands of barbed wire. Charlie CO controlled two vehicle

gates to the base.

140mm rockets. Most of the sentry dogs displayed a specific behavior

pattern or alert whenever there were incoming rockets or mortars.

These few seconds warning was greatly appreciated! We realized the

dog's superior senses were picking up on something, but there was

still an aura of mystique about this. I now realize that it was

just a case of pure Pavlov conditioning. The dog would hear a rocket

either going overhead or on a side of our location, and anticipate

the excitement (handlers become a little hyper when rockets are

exploding about) that always accompanied rockets. One dog Sugar,

would jump up and snap at the air! My dog, Kobuc, would start pulling

to the closest K-9 Fighting Bunker (always knew he was the smartest

dog around!). I only had to crawl; he would navigate.

140mm rockets. Most of the sentry dogs displayed a specific behavior

pattern or alert whenever there were incoming rockets or mortars.

These few seconds warning was greatly appreciated! We realized the

dog's superior senses were picking up on something, but there was

still an aura of mystique about this. I now realize that it was

just a case of pure Pavlov conditioning. The dog would hear a rocket

either going overhead or on a side of our location, and anticipate

the excitement (handlers become a little hyper when rockets are

exploding about) that always accompanied rockets. One dog Sugar,

would jump up and snap at the air! My dog, Kobuc, would start pulling

to the closest K-9 Fighting Bunker (always knew he was the smartest

dog around!). I only had to crawl; he would navigate.  There were 38 normal posts and 40 dog teams available, so two handlers

were off every night. When we were off, we made a night of the movie

theater and club, but we would usually end up at the kennel with

our dogs. Or, we would go out with the Marine squad to an ambush

site. This was always done without the knowledge or approval of

the squadron. We would either catch a ride with the posting truck

or the Marines would send the CO jeep to the kennels to pick

us up. When the squad returned to base the next morning, we would

catch the K-9 relief truck.

There were 38 normal posts and 40 dog teams available, so two handlers

were off every night. When we were off, we made a night of the movie

theater and club, but we would usually end up at the kennel with

our dogs. Or, we would go out with the Marine squad to an ambush

site. This was always done without the knowledge or approval of

the squadron. We would either catch a ride with the posting truck

or the Marines would send the CO jeep to the kennels to pick

us up. When the squad returned to base the next morning, we would

catch the K-9 relief truck.  pick up equipment left on post. He started into the bunker and found

a large Krait snake coiled up, and very unhappy at being

disturbed. Like the Cobra's venom, the Krait's venom is neurotoxic

and signs of paralysis may appear within minutes or be delayed for

hours. That afternoon, I was told about the snake and asked if I

had entered the bunker the night before. I made immediate plans

to treat the smarter member of the team to a steak dinner from the

NCO Club. Kobuc really enjoyed the rare steak I bought him!

pick up equipment left on post. He started into the bunker and found

a large Krait snake coiled up, and very unhappy at being

disturbed. Like the Cobra's venom, the Krait's venom is neurotoxic

and signs of paralysis may appear within minutes or be delayed for

hours. That afternoon, I was told about the snake and asked if I

had entered the bunker the night before. I made immediate plans

to treat the smarter member of the team to a steak dinner from the

NCO Club. Kobuc really enjoyed the rare steak I bought him!